Not only do car and motorcycle accidents have serious emotional and financial repercussions, they can have severe, life-changing physical effects on people as well. New research on the human hormone, progesterone, and its potential link to traumatic brain injuries, however, may offer car accidentsurvivors new hope in alleviating their brain injury symptoms and regaining their quality of life.

No current treatment

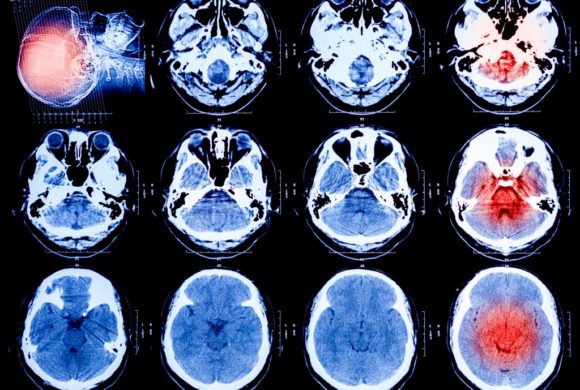

The human brain is a complex mass of cells and each cell works to control some part of the human body and its biological systems. When a person hits their head, and the brain is damaged, it leads to the death or weakening of these cells. If a person suffers a serious brain injury, it means a significant number of brain cells are dead or are in the process of dying. This presents an enormous challenge for physicians as the death of these cells can reduce the amount of oxygen flowing to the heart, lungs and muscles, threatening the life of the patient or leaving them in a comatose or much-altered state.

Currently, there are no curative treatment options for people who suffer from brain injuries and therefore, no steps can be taken to prevent further damage from occurring as cells continue to die. The only options medical professionals have is to monitor TBI patients, facilitate their needs and attempt to prevent further neurological damage from occurring, according to the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke.

Potential breakthrough

Researchers may have found a way to minimize the damaging effects that brain injuries have on victims of car and motorcycle accidents. According to ABC 7 News, researchers believe that the hormone, progesterone, which is most often associated with the regulation of the female reproductive system, has the ability to protect neurons from secondary brain injuries. Progesterone is thought to reduce swelling of the brain, minimize cell death and reconstruct the blood-brain barrier.

A phase three clinical trial is currently in progress to study the long-term possibilities and safety of progesterone on brain injury patients. Patients at 150 locations in multiple countries are given a continuous supply of the hormone for five days, and then rechecked six months after the treatment has ended to evaluation whether there is any marked progression. The study is blind so patients and their families do not know whether they were given the hormone or a placebo and the hormone must be first administered within 8 hours of the injury occurring. Researchers plan to use 1,200 patients with severe brain injury in the global study. If the study is a success, it could become the first real treatment for brain injury.